Is the combustion engine dead?

Answers to this question at the first session of the Leader Forum offered an interesting insight into what we could expect to see in the coming years. The panel consisted of Brian McMurray, VP Engineering and Operations at GM Tech Centre India, Rajendra Petkar, CTO of Tata Motors, Rafiq Somani, Area VP at ANSYS India, and Dr Uwe Dieter Grebe, Global Business Development at AVL, Austria. The debate was meant to figure out the way forward.

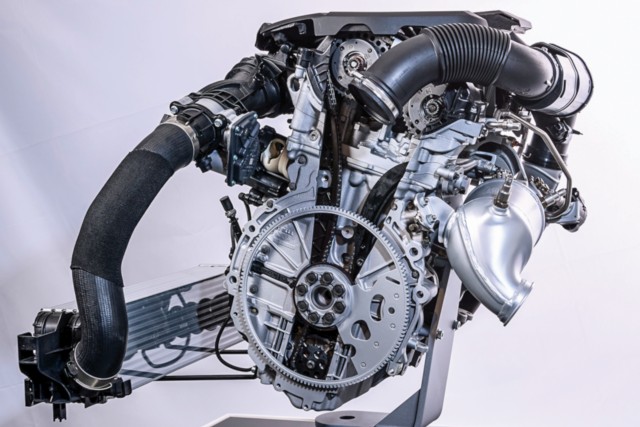

The combustion engine is still a major part of the automobile industry

The first step is to maximise energy conservation and diversification. However, this will only come with a robust system in place, that will be the result of a clear course of action and accompanying policies to act as guides. The point to note is that all forms of hybrid vehicles – battery electric, hybrids, plug-in hybrids and fuel-cell vehicles – use one core set of components: combustion engine, battery pack, control electronics, and electric motors. This makes it easy to mix and match the components and, with larger scale production, it would add to economies of scale. Moreover, a switch to electric vehicles would make no sense without clean, renewable and sustainable energy sources. There’s no point polluting outside the city and then trying to clean up inside it.

If we talk about oil-to-wheel emissions, and also talk about electric cars and battery-to-wheel emissions, there is a significant amount of environmental impact in either case. The move away from rare metals is inevitable. This isn’t because of just the pollution from mining for raw material, but the fact that the finished product, too, has its own shortcomings. Lithium-ion batteries are prone to thermal instability. Solid-state batteries are the next step, but until then the focus of the future will be in synthetic fuels. Essentially, we need to learn from battery technology and figure out a way to use photovoltaic solar energy and wind energy to create synthetic fuel. Until then, maybe till the year 2030 or 2040, the combustion engine will stay. Future norms will not permit only a combustion engine, and, as we discussed in the October 2018 issue of Car India, hybrid is certainly the way to go.

Even mild-hybrids, with smaller, less expensive battery packs, will go a long way in cutting down harmful gas emissions. This would have to be done using down-sized petrol engines for now – solely with the view of keeping costs in check. While diesel hybrid powertrain with advanced emission control technologies such as heated catalysts with turbulent surface structures and AdBlue urea injection for breaking down oxides of nitrogen offer huge potential, bringing all of these technologies to a smaller and more affordable segment in cost-sensitive markets is a huge challenge and will be reserved to larger, more expensive cars for now.

Mercedes-Benz’ OM654 in-line four cylinder turbo-diesel engine is already BS-VI-compliant even with BS-IV diesel fuel

There have been occurrences that almost make it seem that the death of the IC engine is only spoken about to satisfy an urge to be politically correct. Another view is that instead of forcing electrification on to a whole nation with huge diversity, it would be better to identify a few cities and experiment with them as test beds for future electric cities. It would lead to larger scale awareness and prepare for an infrastructure revolution that would spearhead the implementation in more cities in the future.

A full EV eco-system looks like it will take some time, and thus, high priority must first be given to clean and sustainable power generation. We can produce electric cars that are clean but it will only work with renewable energy.

New Toyota Camry Hybrid First Drive Review - Car India

[…] vehicles are the saviours. Not everyone can have unlimited electricity at a throwaway price – not until the technology to […]